Most homeowners receive a property tax bill each November. Renters typically don’t see this bill directly, but their landlords do–and often pass the cost along through higher rent.

What is a Property Tax?

Property tax is a tax on real estate paid by owners of homes, land, and commercial (business) buildings. Property taxes are paid to local governments like counties, cities, school districts, and special taxing districts. Property tax is like a “user fee,” a way for local homeowners and businesses to pay for the community services they rely on.

Each local government sets its own property tax rate. Utah also has a statewide property tax, levied by school districts, dedicated to school funding.

Truth in TaxationUtah has a unique law called Truth in Taxation, which prevents local governments from automatically collecting more property tax money when property values go up. Unlike the state income tax, which has a “fixed rate” of 4.5%, property tax is “revenue-based.” This means:

- Local governments can only collect the same amount of property tax revenue as they did last year, unless they go through a public process.

- If they want more money, they must notify property owners, hold a public hearing, and formally vote to raise taxes.

- Even if home values rise, property tax bills don’t automatically increase. Instead, the tax rate is lowered to keep the total revenue the same–unless the local government chooses to go through the Truth in Taxation process.

The only exception is the Uniform Property Tax Levy, a state-legislature-mandated tax collected by school districts that is exempt from Truth in Taxation rules.

How Property Tax is Calculated

The property tax process involves three main steps:

- Determine Property Values: The county assessor (or, in some cases, the State Tax Commission) determines the value of each property. These values are combined to calculate the total tax base.

- Assess Revenue Needs: Local governments assess how much revenue they need each year and often weigh the political pressure of raising taxes against the need for increased funding. Increasing revenue triggers the Truth in Taxation process, which requires public notice and a hearing.

- Needed Revenue ÷ Total Property Values = Tax Rate: Each taxing entity calculates its own rate, and all of these are combined into a single property tax bill sent annually to property owners.

How Much Do Utahns Pay in Property Taxes?

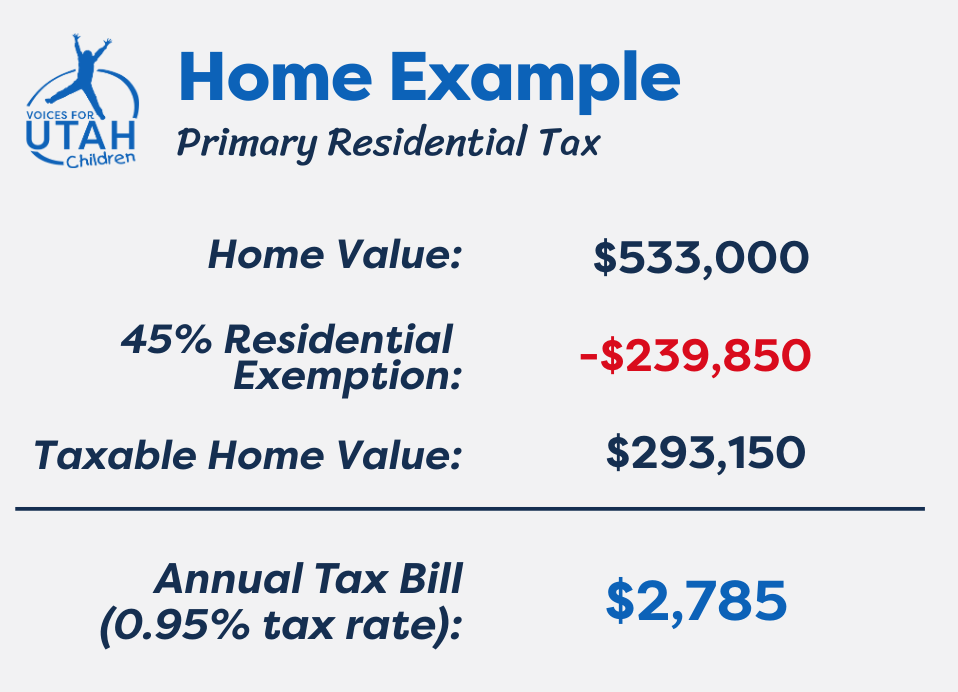

Most property tax revenue in Utah comes from taxes on primary residences–homes where people live full-time. To help reduce costs, most Utah homeowners receive a 45% exemption, meaning they only pay property tax on 55% of their home’s market value. Other types of property–like second homes, rentals, or commercial buildings–don’t get this exemption and are taxed on 100% of their value (with some exceptions for agricultural land).

The statewide property tax rate for residential properties is 0.95%, but many homeowners pay less than that because of exemptions and local relief programs. On average, after exemptions and discounts are applied, Utah homeowners pay about 0.52% of their home’s market value each year in property taxes (this is the “effective” tax rate).

The annual property tax bill for a median-priced home is around $2,785.

How is Property Tax Revenue Spent?

Property tax is the biggest source of revenue for most local governments, and the money goes right back into the community. Property taxes pay for road maintenance, garbage collection, libraries, public parks, and other important services. Local governments also depend on property taxes to fund police departments, fire stations, public water systems, and other critical community services.

Does Property Tax Impact Everyone Equally?

A balanced tax system uses a mix of property tax, sales tax, and income tax to ensure stability, fairness, and responsiveness. Property taxes play a key role in that mix because they tend to remain stable, even during economic downturns, providing a reliable source of funding for schools, cities, and counties.

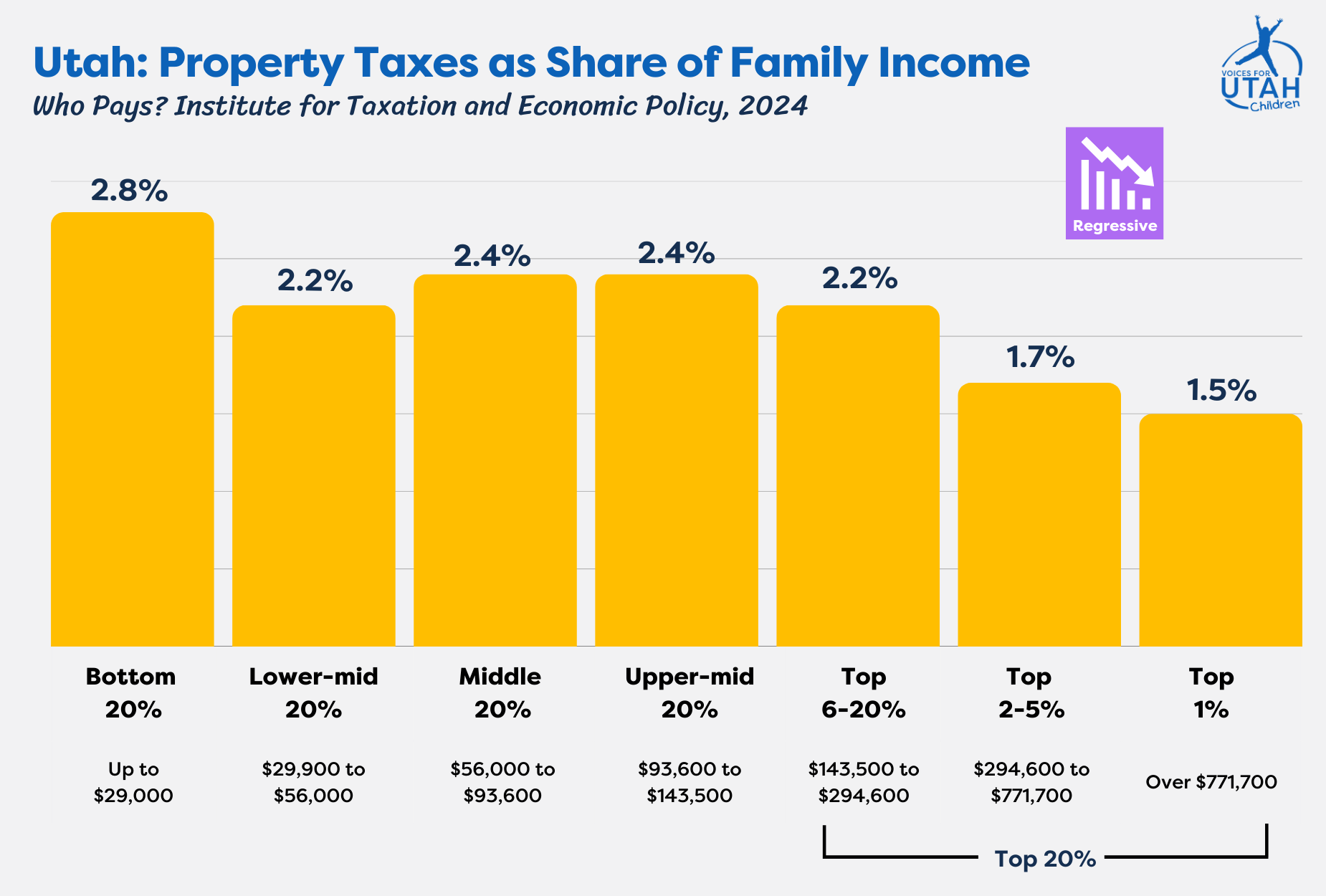

Property taxes can seem fair–people with higher-value homes pay more–but in practice, they hit lower- and middle-income families harder. These families spend a larger share of their income on housing and taxes than rich people. A homeowner earning $50,000 pays the same rate as someone earning $500,000–but the impact on their budget is far greater. The rate is the same, but the sacrifice isn’t.

Property taxes don’t always match someone’s ability to pay. For example:

- Homeowners who lose their jobs or retire still pay the same property tax bill, even if they have less or no income.

- Renters don’t pay property taxes directly, but higher taxes for landlords usually means higher costs for the renter.

- Elderly homeowners on fixed incomes often struggle to keep up with growing property tax bills.

Utah’s Truth in Taxation law also complicates fairness. Local government can’t automatically collect more property tax whenever property values rise. So when property values rise rapidly in wealthier areas, the property tax revenue has to stay flat, unless the local government wants to go through the whole Truth in Taxation process. Over time, people in these wealthy areas contribute an increasingly smaller part of their property value, even as their personal wealth grows. Meanwhile, in less wealthy communities where property values grow slowly or not at all, the local government may need to raise tax rates to maintain the same level of funding.

Analysis from The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy shows low-income Utahns pay more of their income on property taxes than the wealthiest. That’s because housing costs make up a bigger portion of their budget. While wealthier households may own higher-value homes, they also have much more income, so property taxes take up a smaller share overall.

Property Tax & Racial Equity

Historic housing discrimination has long denied communities of color equal access to homeownership and property wealth. Today, families in communities of color often own homes with lower market values–a result of historic and ongoing racism in housing and lending practices–but are still taxed disproportionately more due to overassessment. This means they pay more and get less, reinforcing long-standing racial disparities in public services, education funding, and household wealth.

Are There Any Property Tax Relief Programs?

Yes! Property tax relief programs exist to help homeowners and renters manage high tax burdens. Programs can be found through the local county auditor or treasurer. Some common property tax relief programs include:

- “Circuit Breaker” Credits: Helps those whose property tax payments make up a large portion of their income, particularly low-income seniors and renters.

- Veterans with a Disability Exemption: Offers partial tax relief for veterans with disabilities and their families.

- Active or Reserve Duty Armed Forces Exemption: Full exemption for active or reserve military members who qualify.

- Blind Persons Exemption: Partial exemption for legally blind individuals and their families.

- Indigent Abatement and Deferral Programs: Available for seniors (65+), people with disabilities, or those experiencing extreme financial hardship.

Resources

Annual Tax Reports (Utah State Tax Commission)

Annual Property Tax Reports (Utah Property Tax Division)

A Visual Guide to Tax Modernization in Utah (Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute)

How Property Taxes Work (Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy)

Property Tax Relief (Utah Property Tax Division)

Utah Compendium of Budget Information (Utah State Legislature)

Utah: Who Pays 7th Edition (Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy)